–Hannah Arendt, The Human Condition

If there is a unifying philosophical principle in The Human Condition, it is the principle of conditionality, which holds that human beings are conditioned and conditioning beings. As Arendt explained in the first chapter of The Human Condition: “Men are conditioned beings because everything they come in contact with turns immediately into a condition of their existence…” [1] This principle is diffused throughout the private and public realms, and governs the activities of labor, work, and action. To crib from Patchen Markell’s seminal essay “Arendt’s Work: On the Architecture of The Human Condition,” the principle of conditionality may be understood as the formal design principle of Arendt’s “relational” architecture. [2] Whether human beings are metabolizing nature through labor or transforming nature through work, or acting in concert with one another, human beings are conditioning the material world and being conditioned by it; they live in a contingent relationship with the earth, material things, and each other. With this principle of conditionality, Arendt sought to describe a fragile human ecology — a human way of dwelling in the assemblage of natural and artificial phenomena.

There are three important points to note about Arendt’s principle of conditionality. The first is the mutual vulnerability of humans and their environments. Human beings are not independent of the earth or world; they are earth-bound and world-inhabiting beings who are shaped and habituated by their environments — not absolutely, she reminds us, but enough that we must constantly adapt to new conditions. Even as human beings fashion and change their natural and artificial environments through their actions and innovations, they are impacted by changes they affect. As Arendt put it, “The impact of the world’s reality upon human existence is felt and received as a conditioning force.” [3] Arendt’s description of the “force” of the material world resonates with Bruno Latour’s concept of “actant,” which can be either a human subject or a non-human entity that is capable of modifying other entities through the exertion of a decisive force upon other things in a network as a result of its location in the network. [4] Arendt’s principle of conditionality accounts for this kind of agentic power of natural and artificial entities and reminds us that human beings live in a symbiotic relationship with the earth, world, and other human beings.

The second point to note is that although human beings are capable of a seemingly infinite adaptability, there are limits to what human beings can adapt to. In The Human Condition, Arendt argued that even if human beings were to escape the earth and live under man-made conditions, they would adapt to those new artificial conditions. But Arendt was acutely aware of that human beings can create the conditions for their own destruction, especially through nuclear power. In her 1963 lecture course “Introduction into Politics” at the University of Chicago — which she began working on in 1955 — Arendt acknowledged that human actions could so alter the earth and the world that human beings would cease to exist:

We can conceive of a catastrophe so monstrous, so world-destroying, that it would likewise affect man’s ability to produce his world and its things, and leave him as worldless as any animal. We can even conceive that such catastrophes have occurred in the prehistoric past, and that certain so-called primitive peoples are their residue, their worldless vestiges. We can also imagine that nuclear war, if it leaves any human life at all in its wake, could precipitate such a catastrophe by destroying the entire world. The reason human beings will then perish, however, is not themselves, but, as always, the world, or better, the course of the world over which they no longer have mastery, from which they are so alienated that the automatic forces inherent in every process can proceed unchecked. [5]Arendt recognized that we could so fundamentally change the material world that it would make human existence impossible. Arendt’s principle of conditionality highlights the precarity of our human ecology.

The final point to note is that we are often unware of the conditioning we affect and the conditions by which we are affected. As Arendt pointed out in her remarks at The First Annual Conference on Cybercultural Revolution in 1964, “when the environment has in fact changed, we are conditioned — even if we don’t know that we are conditioned, even though we may know very little about the conditions that have molded us.” [6] This hidden conditioning makes it all the more important to engage in thoughtful action, or as Arendt put it, “to think what we are doing.” [7] Arendt’s recognition of the conditionality of human existence and the limitations of human adaption suggest that we should take care in our actions — that we should consider how our actions are changing the world and how the world may be changing us. This existential imperative is no more relevant than in the looming environmental catastrophe of climate change and the attending crisis of environmental migration.

Climate Change and The Human Condition

It may be surprising to learn that climate change haunts The Human Condition. The book opens with the launch of the Russian satellite Sputnik 1 in 1957, but what has been neglected in most readings of this section of Arendt’s book is that the launch was part of the International Geophysical Year (IGY) project that lasted from July 1, 1957 until December 31, 1958. The IGY was an international scientific research collaboration on geophysics that involved sixty-seven countries. While the launch of Russia’s Sputnik 1, and the subsequent launch of America’s Vanguard 1, were certainly motivated by Cold War strategies aimed at espionage and military intelligence, it also afforded scientists the funding to begin measuring the levels of CO2 in the earth’s atmosphere for the first time. What they discovered was startling: carbon dioxide gas levels were increasing. (Read more about the history of the IGY here). One of the key scientists involved in forming the IGY and measuring CO2 in the earth’s atmosphere was Roger Revelle, who is now known as the father of the greenhouse effect. Revelle, together with Hans Suess, concluded that human actions were increasing CO2 levels and causing the earth to warm at alarming rates, but they were optimistic about the potential for human intervention to slow the effect of global warming. [8] Human beings would need to act more carefully and thoughtfully. Sadly, we have largely ignored their warnings.

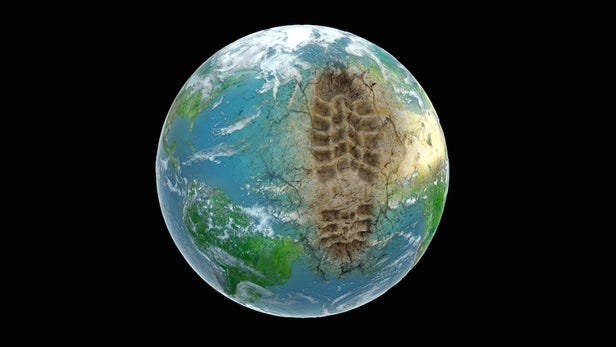

Recently, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change reported with a high degree of confidence that “human activities are estimated to have caused approximately 1.0°C of global warming above pre-industrial levels, with a likely range of 0.8°C to 1.2°C” and that this range is “likely to reach 1.5°C between 2030 and 2052 if it continues to increase at the current rate.” [9] The unfolding consequences for the planet and its human populations are already being felt in increasing land and ocean temperatures, increases in precipitations and sea levels, widespread droughts that destroy agricultural livelihood and lead to human migration, as well as the destruction of ecosystems and species extinction. The long and short of this report is that human activities are changing the earth, and an increasingly warming earth will change human existence. In fact, it already has.

Environmental Migration

Dylan Hollingsworth Photography, 2019

Last year the World Bank reported projected that “by 2050, without concrete climate and development action, just over 143 million people — or around 3 percent of the population across Sub-Saharan Africa, Latin America and South Asia — could be forced to move within their own countries to escape the slow-onset impacts of climate change.” [10] In countries like Honduras, farmers are already being forced to abandoned their farms as a result of failing crops caused by rising temperatures, droughts, and aberrant rainfall patterns — all of which are effects of anthropogenic climate change. With an astounding 70.8 million forcibly displaced persons currently worldwide, we are facing one of the most egregious humanitarian crises in human history, and one of the main contributors to this crisis is anthropogenic climate change.

The Fragility of Life

Dylan Hollingsworth Photography, 2019

Reading Hannah Arendt in the Anthropocene reminds us that everything is fragile. Everything is tied together in a tenuous assemblage of delicate bonds that are easily broken but not easily repaired. Each element of the assemblage — whether natural or artificial — is vulnerable to the influence and conditioning of every other element in the assemblage, and in turn, influences and conditions every other element in the assemblage. Consequently, nothing remains stable; everything is changing. To acknowledge this poignant insight is to acknowledge one’s responsibility to the earth, world, and other human beings. Arendt’s thinking is preoccupied by this insight. Human beings are inextricably tied to everything that exists and these things exert an influence upon them; conversely, human beings also influence everything that exists. Arendt’s principle of conditionality simultaneously asserts the contingency all existing things (e.g., humans, plants, animals, artificial objects) and their value and dignity. Everything has worth because everything is fragile. We would all be better served if we lived more thoughtfully in light of this principle, acknowledging the fragility of all things. Arendt would no doubt recommend that we develop what Martin Hägglund has called a “secular faith” that implores us to “acknowledge the utter fragility of what holds our lives together — our institutions, our shared labor, our love, our mourning — and yet keep faith with what offers no guarantee… It is because our spiritual cause is fragile — because what sustains us can break apart or be shattered — that it matters what we do and how we treat one another.” [11] In the midst of the Anthropocene, we must take care, or everything will fall apart. This is the crisis of our time.