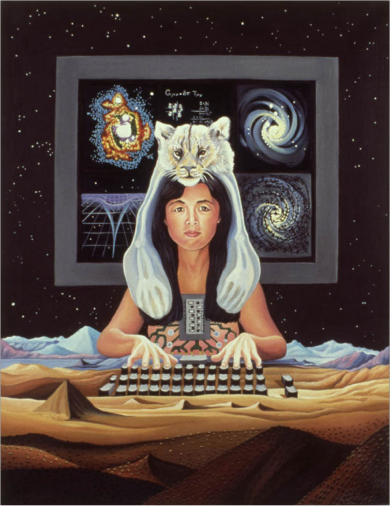

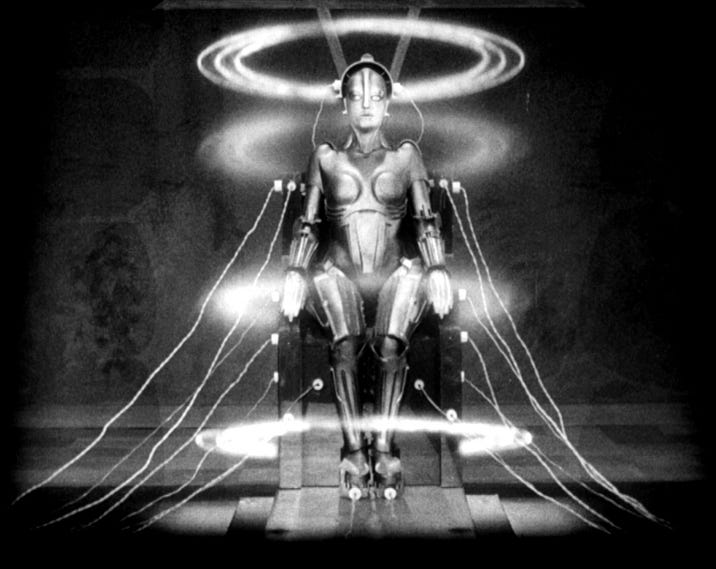

In this way, the graphic detail of the Bard conference icon featured the iron maiden or female Golem prototype of the Maria robot before her rapturous, “singularizing” perfection which transformation gives us the Maria-Robot indistinguishable from the Maria-Mensch or human being.

Lang’s cinematic perfection gives us not any cheaply, ontic technological achievement (a tool that works or “is” everything it appears to be; rather, it offers a “user-friendly” “experience” that we “take” to be the technological achievement of a human machine as such — assuming, that is, that the programming of this illusion also functions and assuming in addition that we, the users, go along with the programming.) The tractable going-along-with on the side of the user just happens to be (and this should be emphasized) the other half of the programming achievement. The point is, as Jaron Lanier writes in You Are Not a Gadget, that it matters less that machines actually are human than that we humans come to see them as human and treat them so. This works, Turing enthusiasts are advised to take note, in both directions.

Of course and at the same time it is relevant that Fritz Lang’s Maria-Robot (Maria enhanced or perfected) turns out to be a filmic simulacrum: not the film technology of filming a robot in accord with the iconic iron maiden phantasm of the movie poster itself. Instead the mechanized robot becomes or is transformed into Maria by way of the theatrical transformation that I above recalled as movie magic. Like the Patty Duke cousin-twins in the American TV series of the sixties, the actress, in this case that would be Birgitte Helm, who plays Maria; the human girl is the same actress who plays the “robot” who looks like a girl because she is one in fact. We are charmed by this movie convention or suspension of belief just as we have learned to love not only Data but Seven of Nine the Borg bot, as we impolitely call her, the Star Trek android, who wears face-jewelry as a fetish signifier of the machine that we “know” her to be.

Thus we get the perfectly archetypal female, and here is a question I would pose to this archetypical notion, so ardently sought by cyborg theorists: would a lady who was and was not a human being (being mechanical, or to employ up-date out terms here: being electronic or simply being a digital representation) but who otherwise fulfilled your every (male) desire, would you (could you?) care less?[17] Internet sex turns out to be just as fulfilling as actual sexual encounters and no awkward after consummation-moments (no discussions, no underwear to find, no Playboy magazine strategies for jettisoning the lady, no having to call or having not to call). Sex with robots would be even better. And who doubts this?

Anders on the Technological Prometheus and the Shame of Having Been Born

We have already mentioned Günther Anders who was Hannah Arendt’s first husband and who was Walter Benjamin’s cousin and to continue the resonance of inbred familiarity, was part of the original circle of young scholars associated with Theodor Adorno and the Frankfurt School in addition to having been a student of Husserl’s and of Heidegger’s. Anders made the question of technological mastery or excess along with the correspondent notion of human obsolescence the center of his life’s work. Anders kept his observant powers throughout his long life, in this not unlike Kant’s late-life productivity, and here we note as variously, disparately gifted human beings, that such a capacity is anything but a given. Nor did Heidegger himself quite achieve this (as Arendt tells us and as Gadamer also attests). But what is still more significant, Anders kept his powers sharply attuned to the changing technological times.Not that this mattered in terms of his lack of influence on the academy which then as now pays attention only to “important” names (and these are usually names we already know). And notwithstanding Anders’ sustained philosophical focus, even philosophers of technology such as Don Ihde and including techno-science and social theorists such as C. Fred Alford do not even mention let alone engage Anders, even Bruno Latour does not do so although Anders is more received in French technoscience than even in German or Anglophone technocience. Surprisingly, even the activist scholar Stanley Aronowitz, himself very like Anders, and whose work is indispensable for a social and political theory of technology, does not refer to Anders, just as those interested in discussing crimes against humanity similarly manage to skip any reference to Anders.

There may be good reasons for this in addition to the perennial scholarly desire to reinvent, all by oneself, whatever it is that one wishes to claim to be the first to talk about or to mention. Or perhaps this was because Anders, like Jacob Taubes, was a pain, difficult to deal with, a bit like Ivan Illich his fellow Viennese, who was however, being a priest, the kinder sort of heretic (Anders, who hailed from Breslau — where Hans-Georg Gadamer grew up, Gadamer, who was born into a German family of scientists and scholars, was born in Marburg — made Vienna his adopted home town with his second wife, Elisabeth Freundlich). If, as can be thought, Anders exemplified such an excessive character it also rendered him well-equipped to deal with similar characters for his own part.

Accordingly, Anders had little trouble dealing with Adorno, a notoriously “difficult” personality. Like Adorno too, it could be observed that Anders was a teaser whose teasing was unbearable for Americans because it pointed out how much he knew and therefore could not but come off as mockery. Unlike the kind of “critical thinking” that involves thinking just and only what status quo science tells you to think, critical theory requires considerable breadth just to be critical. And Anders knew an enormous amount about the Greeks, as he also knew about music, as knew about art, about Hegel and Marx, about Kant, and as he also knew about Husserl and Heidegger. Like Nietzsche and like Illich, the social critic of education, medical science, and technology, Anders was also and this is perhaps the most rare of all, an authentic or real heretic, that is: the sort of critical thinker who meant what he said and who acted on it at the expense of his career- and he did this from the start- and who suffered for this in terms of his reputation (he was for a long time not even mentioned) and his livelihood. Thus, Anders did what most social critics do not do and sometimes even suppose cannot be done: throughout his life Anders walked the talk.

What is more, the views Anders opted to champion were out of kilter, unpopular. Indeed, like Ivan Illich’s political views, Anders’s views were anti-popular. Thus and instead of talking about the Holocaust as a Jew and as he might well have done (though he did this too, he did all kinds of things, including music and literary theory to boot), Anders made Americans (that would be the good guys in World War II from his perspective, and he should have been more grateful…) uncomfortable by talking as incessantly as he did about Hiroshima. And even people who insist on mentioning Hiroshima do not go on, as Anders insisted on going on to talk about Nagasaki and to count off, almost kabbalistically, the dates of Hiroshima, the bomb detonated, as it mattered to him, on August 6, 1945, where just two days later the legal rubric for defining crimes against humanity would be spelled out in Nuremberg on August 8, 1945, the next day Nagasaki, August 9, 1945.

Like Heisenberg, and like Einstein, Anders seemed to think that the problem of evil was the bomb. And like Heidegger he also insisted that the evolution of that same problem had to do with what, unlike Heidegger, he had seen from the start as the problem of humanity itself as standing reserve in Heidegger’s terms, a resource that however would need, desperately need, improving.

This Anders called the shame of being born. This is the shame of a navel. For the mark of creation, as a creation at the hand of god, which is (and here Anders concurs with Sartre) the perfected dream of modernity, is that we as human beings do not merely manage to be the ones who, as Nietzsche’s madman tells us, have “killed” God — “And we have killed him.” (The Gay Science §125) — and with our own hands, so that the sacred as Nietzsche puts it, bleeds to death as we watch (but then, what about the blood, and Nietzsche goes in for excessive realism: what about the stench? Gods, too, so he tells us, decompose!).

Much more than merely murdering God — this, after all, would be a piece of cake for Anders as a Jew, a secular Jew no less — we want to take his place. But that’s the kicker.

The problem for us is that we are born and not made. Above all, we are born, this is the Heideggerian point, as we are born, thrown as we are thrown and we are not designed in accord, this is the anti-Cartesian impetus, with our preferences as we might have specified them (had anyone asked).

Anders’ most dissonant insight — vying with anything Levinas argues about the face as it also vies with anything Heidegger argues about death and thrownness, and with everything (and in the case of Anders this is not by accident) that Arendt writes about natality — is that the whole of our problem with modernity begins and ends with our awful shame at having been born (oh gosh and now we begin to remember all the Theweleit anxieties about war, about Jews and others as very patent anxieties about women). What we and much rather want to be instead, and there is always an instead, is the machine. Anders articulates the modern human fantasy today, the ‘dream’ as he calls it, “was naturally to be like our gods, the apparatus, better said, to belong to these (mechanical) gods completely, to be to an extent co-substantial with these gods: homologoumenōs zēn.”[18] Our desire is to be the machine, or as in the current era, and to speak with Kurzweil, to become one with the digital realm.

Thus and ultimately for Anders, our desire is to be manufactured, to be fabricated, to be a product, maybe one with serial numbers, perhaps an ISBN, just so that we can market and upgrade ourselves: the point here would be interchangeable parts.[19] If something breaks: fix it; when something wears out: replace it.

Thus towards the end of his life, Anders would recollect his own collision with the spirit of the times after World War I. No kind of poetic experience “on horseback,” this was a direct confrontation with changes made by medical technology coupled with modern transport. The result of these technological transformations of human life at the very limit of everydayness, here conceived as a Heideggerian everydayness, shattered that everydayness for him. Beyond anything so theoretically to the point of the ready-to-hand quotidian, more than a misplaced / broken hammer, Anders recalled the dissonance of this vision, at the age of fifteen, as he was on his way home after the first World War, spent as a too-young soldier in France.

On my way back, at a train station, maybe it was in Liege, I saw a line of men, who strangely seemed as if they began at the hip. These were soldiers who had been set on the platform on their stumps, leaning them against the wall. Thus they waited for the train that would take them home.[20]These are transhumans. No one will ever need to tell them that their canes, their wheel chairs, their prosthetic limbs, are their extended selves. This they know.

With this in mind, we quote the little hymn Anders’ gives us for musically-montone Molossians:

But if we ever succeed

in throwing off our burden

and stand as [iron] bars

fitted into [iron] bars

As prosthesis to prosthesisFor Anders, our shame is our genitalia.

in intimate conjoining,

and the flaw was what had been

and shame was yet unknown — [21]

Like Arendt and like Heidegger and Jonas (and so on), we recall that Anders had a classically German classical education, which include both Athens and Jerusalem: thus Anders speaks of aidos. We are, as he says “no product” but and rather than being god — think of Sartre’s very Cartesian, existential articulation of this dream — we are just and merely creatures, with every “creaturely inadequacy.”[22]

Finite and limited, we are merely human. If only we were as gods: if only we could be manufactured to precision standards at the consummate height of the technological engineering we are so sure is coming our way — just you wait.

In the future, everything will be better.

It is Anders’ figural analogy, God = Product, that I find the most compelling or thought-worthy, as Heidegger would say. The product is God. Hence as Anders goes on at this point:

The attempt to prove his “thing piety,” endeavoring an imitatio instrumentorum, one has no choice but to undertake a self-reformation: at the very least and in the smallest degree to undertake effort to “improve” [today advertizing agencies and apologists for transhumanism prefer to say ‘enhance’] himself, rectifying the ‘sabotage’ suffered owing to original sin: the legacy nolens volens of birth, now for once reduced to the smallest conceivable degree.[23]For Anders, we want to correct the mistakes in our make-up: the errors that cause us to become ill, to suffer, to die. An imperfect, rather than a well-made product, as René Descartes had already pointed out as part of his philosopher’s proof of the existence of god (the Parisian theologians did not a miss a beat with this one), a proof that just also happened to be a condemnation of God’s manufacturing specs: had he, Descartes, fabricated himself, he would have done it better.

For Anders, we have already at the time of his writing in the mid 1950’s begun to undertake this same rational and Cartesian enterprise which we call and it is instructive for those who believe like Kurzweil in the logarithmically accelerating evolutionary trajectory of technoscientific engineering and design that we use rather the same terms that Anders emphasizes in 1956, and formulated in English as “Human Engineering”.

As a corollary, so Anders reminds us, the human being is manifestly a “defective design,”[24] especially when regarded from the perspective of technical devices (error tends, as we know, to be “human error” rather than a result of a deficiency in the machine, whatever the machine might be).

In this way, Anders’ first chapter “Concerning Promethean Shame” in the first volume of his The Obsolescence of Humanity: On the Soul in the Age of the Second Industrial Revolution prefigures — albeit in a darker modality — Kurzweil’s brighter enthusiasm for the “natural history,” as it were, of humanity towards an evolutionary culmination in a literally technological rapture. Nor is the word “rapture” an overstatement: we are talking about replacement, consummation, salvation, transfiguration — and like the technical problem attendant upon the theological (or Disneyesque) problem of the resurrection of the body, what do you do with the old phone iPhone when the new one arrives? An already present and growing problem for iPhone owners all over the world in just a few months to the soon to be 5G (ah, the devil take the bees) singularity, some of whom already have two or three earlier phones in a drawer somewhere).

For Anders, Descartes’ musing that God had created him with deficiencies (this would be the true maker’s mark, this would be the Promethean shame), can rightly be kicked up a notch. Here we see that like Arendt, Anders too is Heidegger’s good student, and thus he moves from Descartes to Kant. Thus we move, as Anders argues, “into the obligatory.” Or and in “other words,” as Anders explains, “the moral imperative is now transferred from the human being to the gadget.”[25]

What ought to be, what should be is now the tool, the device, and the gadget. We want technology, the more of it the better, and as we ourselves become our own technology, so much the better. This then is Kurzweil’s dream: let there be not merely the human but high technology, and let us not forget, as we reflect on this, that Kurzweil is in the business of selling technology: let there be stuff to buy.

For his own part, Anders is merely repeating the maxim that Heidegger had already identified in his Contributions to Philosophy as the maxim of fascist techno-science (whatever is technically possible should be actualized as quickly as possible) which as Heidegger had anticipated and Anders could not but corroborate, applied with fairly dispassionate equal measure to Soviet and capitalist aka American science alike:

What can be done counts now as what ought to be done. The maxim: ‘become the one you are’ is today perceived as the maxim of the gadget. … Gadgets are the gifted the ‘whiz-kids’ [English in original] of today [26]But and for all the claims that are made on his behalf (claims Anders happily echoed for his own part) to the effect that Anders opposes Heidegger, just as he similarly opposes Adorno, Anders also takes over (as Adorno also charged) and radicalizes Heidegger’s critique.

Hence Anders begins his 1956 Die Antiquiertheit des Menschen [The Obsolescence of Humanity] with a reflection on nothing other than the very impossibility, as it were, of criticizing technology, that is to say of “refusing” or distancing oneself from technology: an impossibility that found expression for Heidegger himself in his Gelassenheit — and a critical impossibility that has hardly been ameliorated, let us be careful to underscore this, in the interim:

As I articulated this thought at a cultural conference, I was met with the counterclaim, in the end one always has the freedom to turn off one’s technological devices, indeed one even has the freedom to decline to buy any such, and dedicate oneself to the “real world” and just and only this world.As this citation makes plain, Anders follows Heidegger in the case of technology where to follow Heidegger always means, just as Michael Theunissen once reminded us, to be set in contest with him, that means to question as Heidegger questions. In this sense what Anders does is to think Heidegger’s critique as Nietzsche would recommend thinking critique in his own reflections on Kant: through to its furthest consequences.

Which I disputed. And indeed just because the one who strikes is at much as the disposition of technology as is the consumer: whether we play along with it or not, we play along, because we are played. What ever we do or fail to do — that we increasingly live a humanity for whom there is no longer ‚world’ or world experience but phantom of world and a phantom of consumption, no part of this is altered by our private strike: this humanity is today the factical with-world, which we must take into account, to strike against this is not possible.[27]

Thus we recall Heidegger’s allusion to Rousseau at the start of Heidegger’s own The Question Concerning Technology, “Everywhere we remain unfree and chained to technology, whether we passionately affirm or deny it.”[28] Hence when Anders reflects in his The Obsolescence of Humanity on the ultimate impossibility of denying or refusing technology, simply and only because we are human beings in a world with others, he repeats a point Heidegger had underlined early in his Being and Time, writing that “Dasein’s Being in the world is essentially constituted by being with” and underscoring that this remains even when Dasein is alone, “even when factically no Other is present-at-hand or perceived. Even Dasein’s being-alone is being-with in the world.”[29]

But as Heidegger articulates this problem in “The Turn,” one of the original lectures he presented in 1949 in Bremen, warning in perfectly apocalyptic tones attuned to the cybernetic technology of the day and which effects continue on the internet that is the current form of that same broadcast technology: “we do not yet hear, we whose hearing and seeing are perishing through radio and film under the rule of technology. ”[30]

In an age where the Geräte of which Anders speaks, that is, again, the gadgets, the “technologies” as we increasingly speak of them, remain more indispensable than ever they were for Anders writing in what may have been the most optimistic age of technology, that is the postwar era. And this indispensability is not nothing, as Heidegger says. And it is in advance of Baudrillard but very much after Heidegger and in strikingly Heideggerian terms that Anders writes as he does.

As Anders reminds us, no matter what we do, and in this he handily includes every imaginable luddite expedient, we remain constitutionally incapable of renouncing their use:

What holds true of these devices holds, mutatis mutandis, for everything. … To maintain regarding this system of devices, of this macro-device, that is a “means,” that is to say that it is at our free disposal to be set to whatever purpose, would be completely senseless. The system of devices, the apparatus, is our world. And world is something otherwise than means. Something categorically otherwise — .”[31]

In addition to his Heideggerian anticipation of Latour’s claim, as we cited it earlier, that it is difficult to draw the line between us and things, between ourselves and our tools, our technologies, entailing that for Anders we simply “are” the technological things of our lives, Anders ultimate point is a critical one. Thus Anders highlights the already given and determinate character of the modern consumer, determined as we are by our modern advertising. Thus, as we like to say, here making it all-too plain that we speak from the perspective of the advertisers, we live in and on the terms of and as a consumer society. This point is at the same time the very heart of Heidegger’s analysis of Gestell as Anders continues to analyze it, here without reference to the term per se.

For, taken in all precision these are not just so many “preliminary decisions” but the preliminary decision instead. Yes. The. In the determinate singular. For an individual device does not exist — what is at stake in reality is the whole. Every individual device is consequently nothing more than part of a device, merely a screw, merely one piece in a system of devices, a piece partially directed to the requirements of other devices, its existence in part exigent upon other devices which turn compel the necessity for new equipment. [32]

More than Heidegger, although describing Heidegger’s fate as a thinker and critic (heaven forfend!) of technology and indeed (heaven help us still more!) of science, Anders analyses the reasons for our silence as intellectuals in the face of technology and its effects as indebted to nothing more effective and egregious or tragic than simple socialization: in order not to be supposed a reactionary.”[33] Nor has this fear of being thought reactionary (or technologically backward) changed in the interim. Hence Anders’ observation is truer than ever. And his further reflection thus also bears repeated consideration:

that a critique of technology has already become a question of moral courage today is, as a consequence, unsurprising. In the last analysis (so thinks the critic) I can’t afford to permit anyone to say of me… that I was the only one to fall through the cracks of world history, the one and only obsolete human being, and far and wide, the sole reactionary. And thus he keeps his mouth shut.[34]

For just this reason, Anders could not but be a reactionary. Being so got him little for his pains: his work was not read; he was treated with disregard by his peers (and those who were rather less than his peers) in his lifetime. But what he did do was to speak truth to power. And speaking truth to power, even if we never manage to do this for own part, is always something we are always called to do — even on pain of being “far and wide, the only reactionary.”[35]

Anders took this further than it took Heidegger but it also took him further than Adorno with whom Anders remained in contact, however bristly contact. Thus to illustrate my conclusion to follow, Anders reminisced, recalling a phone call he made to Adorno to ask Adorno if might stand in his place in a protest action Anders could not attend. Adorno predictably responded by refusing, somewhat indignantly: You know I don’t follow any banner. Anders reply was point-counterpoint: Then run ahead of it.

Adorno hung up. There was, because there could be, no reply to that.

Conclusion

When it comes to technology, to machines and the question of (human) mastery, I maintain the Andersesque hope that and unlike Adorno who simply heard Anders’ suggestion as an insult,[36] that we might yet find ourselves willing to take up the charge, and may be even, as Anders suggested, to take the lead in a moment of human freedom.As we recall from Heidegger’s The Question Concerning Technology, “Everywhere we remain powerlessly chained to technology, whether we passionately affirm or negate it.”[37] Heidegger’s language includes the term “unfrei,” with all of its Rousseauian overtones. The very same point recurs on the first page of Marcuse’s One Dimensional Man and for his part, Anders himself reflects in 1956 in the Obsolescence of Humanity that it is impossible simply to renounce technology for the very early Heideggerian reason that we are human beings in a with-world, Mit-Welt, with others, Mit-dasein.

The problem that remains is the particularly Marxist and critical challenge of action. And Anders, more than either Heidegger or Adorno, was a scholar who acted on his politics, as radically conceived as they were, in the real world, the life of human action. And what often goes by the title of political agency, be it reading the paper, voting in a two party system, everyday politics of whatever given public sphere, should be contrasted with Anders’ activism as this last involved the kind of life action that would seem to have been technologically eclipsed until the events sponsored, aided and abetted by technology, that would be the role, however short-lived in the end, in the Arab spring or the still ongoing American Fall into Winter, OWS. For the most part however, for most of us, especially we academics, we think ourselves “activists” if we click on an email link and hit return.

As Heidegger never tired of reminding us, down to a last letter that was also the last academic reflection he would write, to a circle of American Heidegger scholars: we still need to question in the wake of modern technology.